Sheet Metal Forming Techniques

Sheet metal is an important and popular component of modern manufacturing. It is used in domestic appliances, cookware, car doors, door handles, and more sophisticated machine parts. The art of creating these parts, components, and assemblies using sheet metal is known as sheet metal fabrication. This process consists of techniques or methods such as cutting, forming, joining, assembling, and finishing to achieve the desired component.

Sheet metal forming is one of the most essential fabrication processes. It involves deforming the metal without adding or removing material. This article covers all you need to know about sheet metal forming, its definitions, a detailed explanation of its processes, and the considerations before using forming for your project.

What is Sheet Metal Forming?

Sheet metal forming is a fabrication process that involves the reshaping of sheet metals into a part of the desired geometry by applying forces such as tension and compression. This transformative sheet metal manufacturing process is carried out and completed without cutting or boring any part, maintaining its mass. Sheet metal forming is one of the most important processes in the modern fabrication of parts and components. Through the forming process, the metals' plastic characteristic allows the metals to be deformed into different desired shapes while still maintaining their structure and integrity. The process employs techniques like bending, stretching, and pressing to create components with high precision.

Sheet metal forming is ubiquitous in manufacturing because of the favourable properties of materials like steel, aluminium, brass, and copper, which combine strength and malleability. These characteristics enable the creation of lightweight yet durable parts suitable for various uses. Additionally, the process is typically cost-effective, particularly for simple designs and standard sizes, compared to alternatives like forging or metal stamping. The choice of forming methods depends on factors such as the metal type, design complexity, and production volume. High tooling and labour costs often make it more efficient for large-scale production, where economies of scale can be achieved. Techniques such as punching, press braking, rolling, and extrusion rely on the plasticity of metals to shape them while maintaining structural integrity.

Types of Materials Used in Sheet Metal Forming

Material selection in sheet metal forming is a critical decision that directly impacts the final product's manufacturability, functionality, and durability. The choice of material must align with the application, mechanical properties, and environmental conditions. Below are the materials commonly used in sheet metal forming, their properties, and applications:

- Stainless Steel – High strength, corrosion-resistant, and malleable. Used in medical devices, food processing, kitchenware, and architecture. Grades 304 and 316 (superior chemical resistance).

- Aluminium – Lightweight, high strength-to-weight ratio, and corrosion-resistant. Ideal for outdoor, marine, and intricate designs.

- Hot-Rolled Steel – Cost-effective, flexible, and easy to fabricate. Used in construction, automotive frames, and railway tracks. Rough surface, less precise than cold-rolled steel.

- Cold-Rolled Steel – Stronger than hot-rolled steel with improved surface quality and dimensional accuracy. Used in structural components, household appliances, and aerospace.

- Galvanised Steel – Zinc-coated for corrosion resistance. Common in roofing, HVAC, refrigeration, and agricultural machinery. Durable and cost-effective.

- Copper – Excellent electrical/thermal conductivity and antimicrobial properties. Used in wiring, busbars, heat exchangers, and medical applications. Brass (copper-zinc alloy) offers better machinability and aesthetics.

- High-Strength Low-Alloy (HSLA) Steel – Stronger and lighter than carbon steel. Used in automobiles, bridges, cranes, and heavy machinery. Reduces weight, improving fuel efficiency.

Sheet Metal Forming Processes

Sheet metal forming involves shaping metal sheets into desired geometries without removing material. This process involves several different techniques that achieve widely varying shapes. Each sheet metal forming process involves specialised procedures and machinery.

Bending

Bending is one of the most popular metal sheet forming processes. It is done by applying force along the straight axis of the sheet metal, making it bend at an angle. This operation is performed without cutting or punching material, preserving the volume and typically maintaining the sheet's thickness. Bending is usually carried out by a machine called a press brake. It can be operated automatically or manually and is available in sizes 20-200 tons, matching the application. The press brake comprises an upper tool called the punch and a lower one called the die, between which the metal sheet is placed. The angle of the bend is determined by how deep the punch forces the metal sheet into the die. Bending applications include the fabrication of brackets, enclosures, automotive components, and various architectural features.

This sheet metal forming process has various techniques. It can be categorised into several types based on the technique and equipment used:

- V-Bending: This technique can be further divided into two different types:

- Air Bending: Involves partial contact between the die and workpiece, allowing flexibility in achieving different bend angles using a single toolset.

- Bottoming (or Bottom Pressing): The sheet metal is pressed entirely into the die, resulting in precise and repeatable bends.

- Coining: A high-force bending method where the workpiece is pressed into the die, creating highly accurate bends with minimal spring back.

- Roll Bending: This is ideal for forming cylindrical or curved shapes, using a series of rollers to bend the sheet gradually.

- Wipe Bending: This uses a punch and die to create bends where the material is clamped along its edges.

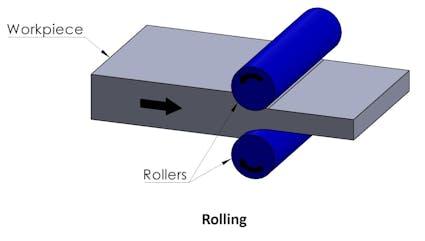

Rolling

Rolling is a metal forming process in which a flat sheet continually passes through a series of roll stations. Each station contains paired roller dies, progressively shaping the sheet into the desired profile.

The process helps form complex cross-sectional geometries with high dimensional accuracy. Rolling is mainly used to manufacture roofing panels, structural beams, and storage shelves. types of Rolling Processes:

- Flat Rolling: This produces uniform sheets and plates by compressing the metal between two rollers.

- Shape Rolling: Forms specific cross-sectional shapes such as channels, I-beams, and T-sections.

- Ring Rolling: Expands the diameter of a ring-shaped workpiece using rollers, commonly applied in manufacturing flanges and bearings.

- Thread Rolling: This creates threads on cylindrical surfaces by rolling the material between dies.

- Hot and Cold Rolling: Hot Rolling is performed above the metal's recrystallisation temperature, while cold Rolling occurs below it, offering enhanced surface finish and dimensional precision.

Curling

Curling adds a hollow, smooth, circular roll to the edges of sheet metal, eliminating roughness and sharpness. This process is carried out by feeding the sheets into machines that slowly roll and bend those edges into smooth shapes. Curling not only enhances edge strength but also improves safety and usability. It is commonly applied to parts requiring tubular or rolled edges, such as door frames, can edges, or decorative trims.

Extrusion

This sheet metal forming process involves forcing and compressing the metal through a die to create long pieces with uniform cross-sections. It can be performed using hot or cold methods and is versatile in producing components with complex profiles, including window frames, automotive trim, and lightweight structural components. Variations of this sheet metal forming process include:

- Direct Extrusion: The billet is first loaded into a container with die holes and then pushed through the die in the same direction as the punch. This action causes a lot of friction, leading to wear.

- Indirect Extrusion: The die compresses the billet, reducing friction and tool wear.

- Hydrostatic Extrusion: Uses pressurised fluid to push the metal through the die uniformly.

- Tube Extrusion: Produces hollow components like pipes and cylinders.

Stamping

This sheet metal forming process generally produces large volumes of identical metal components. It is a very close, effective, and high-speed process. For this process, sheet metals, called blanks, are loaded into a stamping press, where a tool and die interface exert force to reshape the material into the intended form. Stamping processes can be executed as independent operations or combined with other sheet metal forming methods, allowing them to be effective for short and long production cycles. Stamping presses with capacities that can handle up to 400 tons can produce components as thin as 0.005 inches while maintaining tolerances.

Stamping sheet metal is widely used in mass production of parts. It is valued by many industries for its efficiency, consistency, and ability to produce complex geometries with tight tolerances. This process plays a crucial role in modern manufacturing, whether for small intricate components such as steel plates and door handles or large structural parts like car doors and machine parts.

Ironing

Ironing achieves uniform wall thickness in components by passing the metal through a narrow clearance between a punch and a die. Commonly used in producing beverage cans and containers, this process enhances strength and reduces weight without compromising volume.

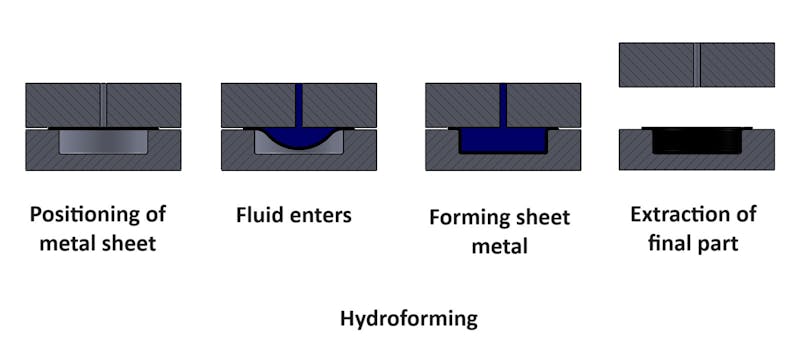

Hydroforming

In this process, the metal sheet is stretched by a highly pressurised fluid over a die to create curved or hollow forms. It's especially effective with malleable metals such as aluminium, producing strong structural components while preserving the material's original qualities. The procedure involves securing a metal sheet over a die and sealing it within a hydraulic chamber. The metal is pressed into the die by pumping fluid at high pressure to achieve its final shape.

Hydroforming can efficiently produce parts with consistent thickness and minimal scrap, leading to cost-effective solutions for complex designs in sectors like automotive, medical, and aerospace. However, the initial costs for hydroforming machinery and die creation can be significant.

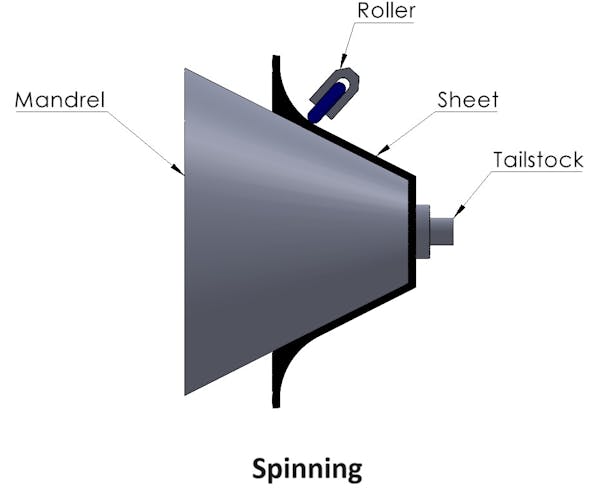

Spinning

Spin forming is also called the sheet metal forming process, which is utilised to form rotationally symmetric parts by pressing a rotating sheet metal blank against a tool called the mandrel using rollers. It is used for cookware, satellite dishes, and musical instruments. This process has two spinning methods, namely;

- Conventional Spinning: In conventional spinning, a roller tool presses against a blank, shaping it to fit the contour of the mandrel. The finished spun part will have a smaller diameter than the original blank but keep a consistent thickness. Maintains constant material thickness while shaping.

- Shear Spinning: The roller curves the blank around the mandrel and exerts a downward force while moving, stretching the material over the mandrel. As a result, the outer diameter of the spun part stays the same as the original diameter of the blank, but the wall thickness becomes thinner. This reduces wall thickness during forming.

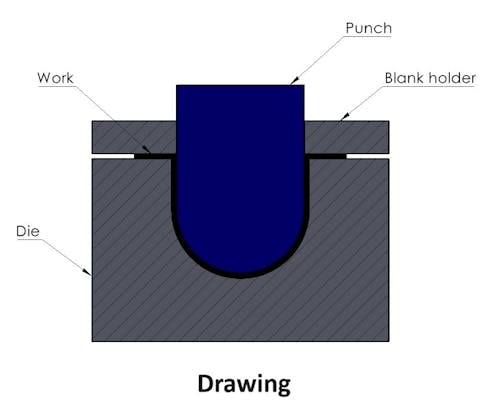

Deep Drawing

Deep drawing stretches sheet metal into deep, cup-shaped components. The process uses a punch and die and is suitable for producing parts with a depth greater than half their diameter. The deep drawing process involves several key components: a blank, a blank holder, a punch, and a die. The blank is a pre-cut piece of sheet metal, usually in the shape of a disc or rectangle, intended for forming into a final part. The blank holder secures the blank over a die with a cavity shaped like the final product. A punch then moves downwards, stretching the material into the die cavity.

Hydraulic systems typically power this punch to exert sufficient force on the blank. Both the die and punch undergo wear due to the pressure exerted during the process, which is why they are constructed from durable materials like tool steel or carbon steel. Applications include automotive panels, kitchen sinks, and beverage cans.

Stretch Forming

The sheet metal is stretched and bent over a die, forming wide contour parts. Stretch forming stretches and bends sheet metal over a die to create large, contoured parts. Stretch forming is a stretch press process where a metal sheet is clamped along its edges by gripping jaws. These jaws are connected to a carriage that uses pneumatic or hydraulic power to stretch the metal sheet. A solid, contoured tool known as a forming die acts as a mould for the sheet. Typically, stretch presses are designed vertically; the form die is positioned on a table that rises to press against the sheet, causing it to deform under tension. There are also horizontal stretch presses, where the form die is mounted sideways, and the sheet is pulled around it. It is commonly used in aerospace for fabricating aircraft skins and in automotive industries for door and roof panels.

Important Parameters in Sheet Metal Forming

Several key parameters influence the quality, precision, and efficiency of sheet metal forming processes. Understanding and controlling these factors is essential for achieving optimal part performance, minimising defects, and ensuring cost-effective manufacturing.

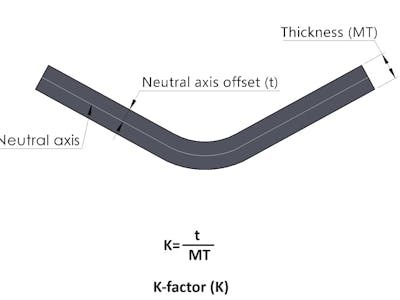

K-Factor

The K-Factor determines how much steel material is displaced after bending. High K-factor values show that much material is stretched in the bend area. During bending, the outer layers of the sheet stretch while the inner layers compress. The neutral axis is the point where no stretching or compression occurs.

The K-Factor varies depending on the material type, thickness, and bend radius and is crucial for producing accurate and consistent angular bends.

Formula; K=tT

Where;

t = Distance from the inner bend surface to the neutral axis

T = Sheet thickness

Typical K-Factor Values:

- Soft materials such as Aluminum and mild Steel: 0.33

- Harder materials like Stainless Steel, Titanium: 0.40 - 0.50

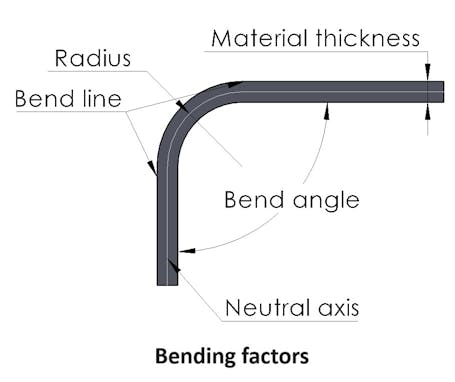

Bend Radius (R)

The bend radius is the inside radius of a bend. It helps determine the amount of bending stress exerted on the material, the chances of cracking (in harder materials), and the springback effect after bending. Smaller bend radii lead to higher stress concentrations. Mild steel can have small bend radii, but brittle materials must have wider bend radii to avoid failure.

This consideration is critical for effective sheet metal welding after forming. Bend Radius recommendation (as a multiple of thickness, T):

- Mild steel: 1.0T - 2.0T

- Stainless steel: 2.0T - 4.0T

- Aluminium alloys: 1.5T - 3.0T

Bend Deduction (BD) and Bend Allowance (BA)

Bend deduction is the length lost as a result of the curve, whereas bend allowance is the extra length of material required in the flat pattern to accommodate the bend. Both elements are essential to guarantee that the part's final dimensions are precise and that the necessary tolerances are fulfilled. These values can be found using various charts and algorithms based on bend characteristics and material parameters.

Formula:

- Bend Deduction (BD):

BD=2*(R+T)tan2-BA - Bend allowance

BA=(R+K+T)

Where:

θ = Bend angle (in radians)

R = Inside bend radius

K = K-Factor

T = Material thickness

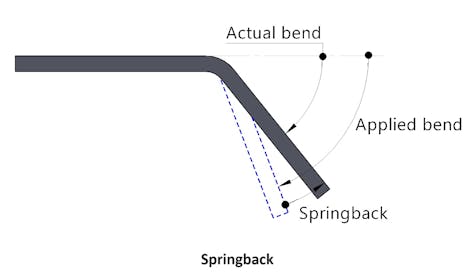

Springback

Springback is the tendency for a material to partially return to its original shape after removing the bending force. The amount of springback can depend on the material properties, the bend angle, and the degree of plastic deformation. Springback affects the final part dimensions and must be compensated for during forming.

Manufacturers often compensate with an intentional over-bend during the forming process, which requires a deep understanding of the material's behaviour . Factors affecting springback include:

- Higher bending angles increase the springback

- Thicker materials experience more springback

- The smaller the bending radius, the more the springback

- Higher yield strength of the material leads to higher chances of springback

Die Clearance

Die clearance is the gap between the punch and die during the Sheet Metal Forming processes. Not enough clearance can lead to excessive stress and damage, while too much can cause poor edge quality and increased scrap rates. To get the required results, die clearance must be adjusted according to the thickness and qualities of the material.

Formula: for (C):

C=P-D2

Where:

C = Die Clearance

P = Punch diameter

D = Die opening diameter

Die Clearance Recommendation:

- Soft materials (aluminium, copper) → 5-10% of material thickness

- Mild steel → 10-15% of material thickness

- Stainless steel or high-strength alloys → 15-20% of material thickness

Holding Time

Holding time is the duration over which pressure is maintained on the material during the sheet metal forming operations. This period allows the material to adapt to the shape of the die and can significantly influence properties such as surface finish and dimensional accuracy. Optimising holding time can improve the effectiveness of the forming process, reduce defects, and enhance overall product quality. Holding time is particularly important in deep drawing to improve material flow, reduce tearing, coining, and embossing to enhance accuracy and detail, and in hot forming processes to transform uniform grain structure.

Sheet Metal Forming Considerations

When considering the sheet metal forming process, you have to consider several key factors that would affect the process's efficiency and the quality of the final product. A clear understanding of these factors is essential for optimising the process. Geomiq meticulously implements these considerations, ensuring we deliver top sheet metal fabrication services. Join us on the path to better, faster and stronger innovation.

1. Material Considerations

The properties of the material directly impact its behaviour during the forming process. Important considerations include:

Ductility:

Ductile materials such as copper, aluminium, and low-carbon steel are more suitable for sheet metal forming as they can undergo significant deformation without cracking. Meanwhile, brittle materials require other specialised techniques to be adequately fabricated to avoid failure.

Grain Direction (Anisotropy):

The orientation of the metal's grains affects its strength and formability. Note the grain direction before you start the forming process. Working along the grain direction increases the risk of cracking, while working across or at an angle to the grains ensures better performance.

Heat Treatment:

Proper heat-treated materials offer improved ductility and reduced residual stress, making them easier to form. However, hardened or cold-worked metals may require higher forming forces and careful handling.

2. Size Considerations

The dimensions of the sheet metal to be formed are crucial in determining the sheet metal formation.

Thickness:

Thicker sheets need more force during forming, potentially limiting the complexity of shapes. Therefore, consider using other techniques if you are working with thicker-sized parts. Thinner sheets are easier to shape but are more prone to tearing, wrinkling, or distortion.

Length and Width:

Larger sheets pose challenges for uniform deformation, consistent force application, and handling, often requiring specialised equipment.

Aspect Ratio:

Parts with a high aspect ratio may experience uneven deformation or localised thinning, necessitating additional design or process adjustments to mitigate defects.

3. Load-Bearing Capabilities

Effective management of the applied forces during formation is necessary to maintain the material's integrity and prevent defects:

- Tensile Strength: Greater forming forces are needed for high-strength materials, which might limit the complexity of parts that can be made and increase tooling wear.

- Springback: The material's elasticity permits it to partially regain its original shape after forming. Dimensional correctness is ensured by appropriate tooling modifications or compensation during design.

- Load Distribution: Uniform application of forming forces is crucial to ensure constant component quality and avoid localised thinning or ripping.

4. Design Considerations

The design of the sheet is an important factor in determining how best to go about the sheet metal forming. Taking into account these considerations would ensure reduced defects and increased cost efficiency. Key design aspects include:

- Parts with Holes: Punching and laser cutting operations are advisable before forming parts that are meant to have holes. It would prevent misalignment or distortion during deep drawing and bending.

- Complex Geometries: Progressive dies or multi-step forming processes may be required for intricate shapes.

- Bend Radius: The minimum bend radius must be higher than the material thickness to avoid cracking. Sharp bends or tight radii can lead to failure, so they should be minimised unless supported by advanced forming techniques.

- Hole Placement: Holes on the sheet are to be located away from the bends and edges to avoid tearing and stress concentration. Adequate spacing between holes ensures the structural integrity of the part.

- Relief Features: Relief cuts or notches can minimise stress in high-deformation areas, improving material flow and reducing the risk of cracking.

- Material Flow: Designing parts to promote uniform material flow during forming reduces the risk of thinning, wrinkling, or uneven deformation. Features like ribs or beads may be added to strengthen the structure and aid formability.

Conclusion

Sheet metal forming is a versatile manufacturing process used across various industries to create precise, durable, and functional components. Selecting the right material, process, and parameters is crucial for achieving optimal performance while minimising defects and production costs. Factors such as material ductility, grain direction, heat treatment, and geometric considerations significantly impact formability and final part quality.

By carefully evaluating load-bearing capabilities and design constraints, manufacturers can enhance efficiency, reduce waste, and improve structural integrity. A well-optimised sheet metal forming process ensures high-quality results, making it a reliable solution for modern engineering and production needs.

About the author

Sam Al-Mukhtar

Mechanical Engineer, Founder and CEO of Geomiq

Mechanical Engineer, Founder and CEO of Geomiq, an online manufacturing platform for CNC Machining, 3D Printing, Injection Moulding and Sheet Metal fabrication. Our mission is to automate custom manufacturing, to deliver industry-leading service levels that enable engineers to innovate faster.