By Danielle De La Bastide

For the patient, healing and adapting to a new prosthetic can come with complications of its own, some arising from a bad fit. According to Raconteur, 16 per cent of patients surveyed by NHS England complained the most about socket fit.

Creating a cheaper and adaptable interface between the residual site and artificial limb can help normalise life post-amputation. Additive manufacturing (3D printing) has become a tool needed to achieve this goal.

There have been many stunning developments in the medical manufacturing arena, most notably in the field of prosthetics. Recently, researchers from the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Department for Health and Centre for the Analysis of Motion, Entertainment Research and Applications (CAMERA) at The University of Bath have combined computer science and innovative manufacturing to create custom prosthetic liners in under one day.

At the outset of an amputation, the residual limb tends to change shape during the 12 – 18 months of healing time. The current silicone liners offered to connect leg or arm to prosthesis can fail to adjust, causing the amputee to add more layers for comfort and to prevent tissue damage.

Additive manufacturing uses 3D technologies to create bespoke devices in numerous materials quickly. For the medical community, these methods make for a smooth collaboration due to the rise in demand for more streamlined production and delivery of medical products.

“We hope to demonstrate this approach is economically viable for use in the NHS and believe this can reduce the burden and costs on the NHS as well as dramatically improve the quality of life of amputees using prosthetics,”

Currently, implants that used to take weeks to produce now take hours with 3D printing methods due to the reliance on computer-aided design (CAD) software. CAD removes the need for creating physical models that can take weeks to produce, and instead uses real-time data from 3D scanners.

The research team leveraged this process to create a prosthetic liner that is both cost-effective and long-lasting.

“Using a state-of-the-art scanner which quickly captures 3D shape, the research team precisely scans an amputee’s residuum. The scanned data is then used to create a full digital model of the residuum, which is subsequently used to design the personalised liner. The liner is then manufactured using a cryogenic machining technique, negating the need for complex and time-consuming moulds,” states a press release from The University of Bath.

Typically, an amputee would have to visit their NHS centre multiple times during recovery to refit their liner. The technique proposed by the research team is expected to reduce the time spent using NHS resources by providing the patient with a series of custom liners sized according to the growth of the residual limb.

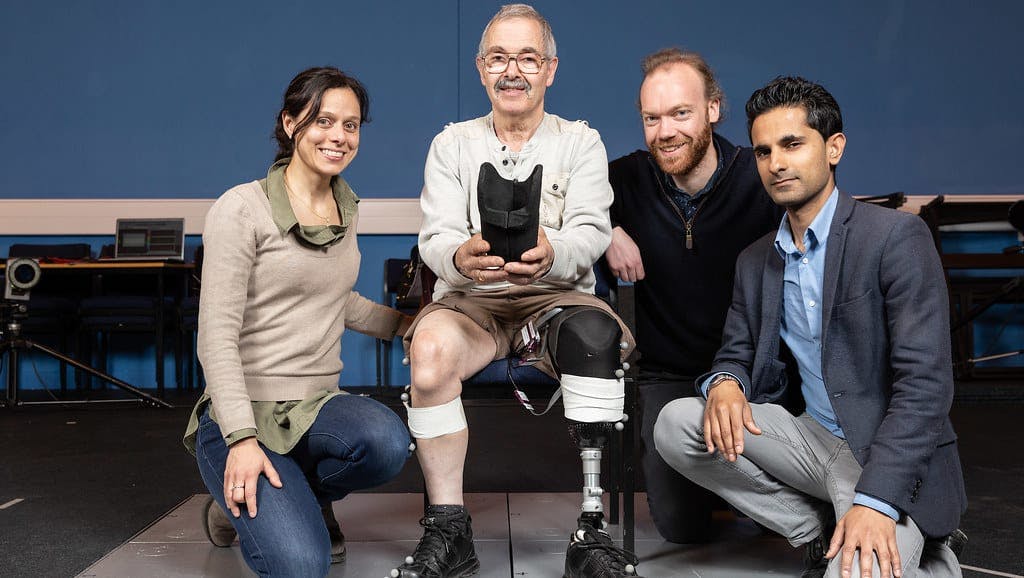

L-R: Dr Elena Seminati, John Roberts, Matt Young and Dr Vimal Dhokia

With this process in development, the team hopes to expand their new techniques outside the university walls.

“We hope to demonstrate this approach is economically viable for use in the NHS and believe this can reduce the burden and costs on the NHS as well as dramatically improve the quality of life of amputees using prosthetics,” concludes the report.

In the next few years, medicine and manufacturing on-demand (MOD) like 3D printing will only continue to collaborate, through the use of neural integrations, software improvements and socket technology. The future of MOD is set to expedite the treatment process and simplify the supply chain by producing custom materials accurate to the minute detail. With real-time data, manufacturers can begin building prototypes immediately and have parts sent to the client in the same day.

In the future, obtaining a custom prosthetic won’t be as arduous or costly; the status quo could develop into patients printing a liner or limb themselves.